What is a “sense of place” and why does it matter?

What role does place attachment have in the Exit 9 transition to a better life?

"To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul." Simone Weil

When we moved to Vermont, Jim bought heather, which he wanted to plant in a specific spot. Now, heather needs moist, well-draining, slightly acidic soil in a sunny spot, and unfortunately, where we planted it, it got none of that. Not surprisingly, it didn’t last long.

Because I’m a gardener, I think “grounding” or “being rooted” is a perfect metaphor for the importance of place attachment. Every gardener knows that plants need the right conditions to grow—the right soil, sun, and water. But we don’t consider with enough conviction that people are the same way—as with plants, the environmental conditions have to be right for a person to thrive and flourish.

I believe the unique conditions required for human flourishing are not taken seriously enough, which may explain why so many people feel unmoored and disconnected today.

The promise of Mile Marker 5: As you pull away from the highway, you will follow the off-ramp to the place of your heart’s true home. There, you will find connection and belonging. The very landscape will be your constant wellspring of satisfaction and joy.

What is a sense of place?

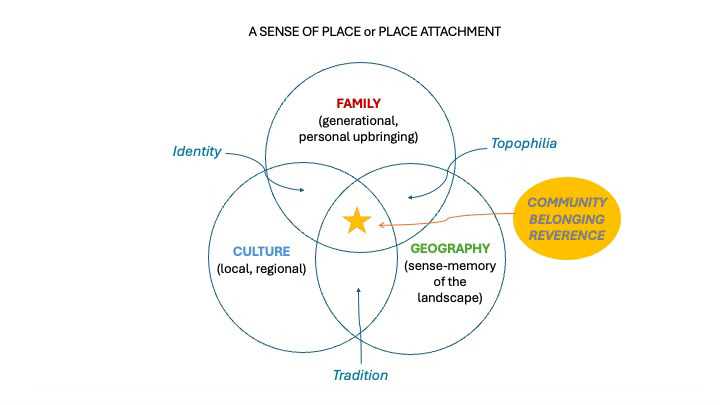

A sense of place is not just one thing, any more than a cake is just flour. It is a complex—partially objective, partially subjective—set of layers of personal experience, local culture, and geography.

Here is a Venn Diagram I’ve created to illustrate the elements of a sense of place. The basic ingredients of this “recipe” are Family, Culture, and Geography.

Family+Culture gives you IDENTITY.

Culture+Geography gives you TRADITION.

Geography+Family gives you that strong bond that connects nostalgia with a sense-memory of the landscape—captured in the word popularized by geographer Yi-Fu Tuan—TOPOPHILIA.

All of these—identity, tradition, and topophilia—come together to provide you with a profound sense of COMMUNITY, BELONGING, and REVERENCE for the world that surrounds you.

True story: I once wrote a deposit check for an apartment rental within an instant of catching a waft of a sea breeze during the walk-through, which immediately evoked memories of my idyllic summers at my great-aunt’s beach cottage. Family, culture, and geography congealed in one waft and ignited a yearning I couldn’t ignore.

Place attachment isn’t necessarily the place of one’s origin. Many people find their true home far from where they grew up. Georgia O’Keefe, for example, came of age in the upper Midwest, developed her art in New York City, but found her true self in New Mexico.

On the other hand, Wendell Berry and bell hooks tried their hand out in the world for their education and early careers but found compelled to return to the home of their birth. Kentucky is the shared homeland they not only returned to, but wrote prolifically about, in their books and poems. (There must be something about Kentucky!)

For bell hooks, her sense of place had roots in her community of shared values:

In all the places I journeyed to in an effort to become that ‘better’ human being away from my Kentucky home, I confronted a culture of narcissism, one in which spiritual beliefs and ethical values had very little meaning for most folk. I longed to find in those places the values that I had learned in my growing years. Simple values had grounded my sheltered life. Taught first and foremost to be a person of integrity, to love one’s neighbor as oneself, to be loyal and to live at home on the earth, I did not know how to live in a world where those values had no meaning. — bell hooks, Belonging: A Culture of Place

For Wendell Berry, his sense of place is rooted in his life as an agrarian, which he has described as a particular ecosystem of economic and communal needs—a way of life now too often under siege from a culture of detachment. In his own life, he has steadfastly upheld the tradition and culture of his land—rejecting most technologies, and remaining critical of political and social changes that have dismantled self-sustaining ecological and cultural norms.

The old complex life, at once economic and social, was fairly coherent and self-sustaining because each community was focused upon its own local countryside and upon its own people, their needs, and their work. That life is now almost entirely gone. It has been replaced by the dispersed lives of dispersed individuals, commuting and consuming, scattering in every direction every morning, returning at night only to their screens and carryout meals.

― Wendell Berry, The Art of Loading Brush: New Agrarian Writings

The importance of a sense of place

It is hard to define the value that the feeling of rootedness brings.

You can’t easily compute a financial ROI for returning to a land that is calling to you. You can count the number of bars, museums, and bookstores, but will that add up to the incalculable sense-memory of a soul-enriching landscape?

It might be walkable, but is it lovable?

In This Place on Earth: Home and the Practice of Permanance, Alan Thein Durning relates his roundabout journey to his real home. His lightbulb moment occurred when he was asked a simple question by a Philipino peasant: “What is your homeland like?”

She repeated the question, thinking I had not heard. ‘Tell me about your place.’ Again, I could not answer…The truth was I lacked any connection to my base in Washington, D.C., and for some reason, for the first time, it shamed me. I had breakfasted with senators and shaken hands with presidents, but I was tongue-tied before this barefoot old woman.

‘In America,’ I finally admitted, ‘We have careers, not places.’

Looking up, I recognized pity in her eyes. —Alan Thein Durning

The benefits of being rooted in the right place

The health benefits of “the vibe”

You may choose a place to live because it’s good on paper—it’s affordable, close to your job, it meets basic needs. But the more ineffable qualities—the ones hard to put on paper or easy to ignore—might be the most important contributors to your well-being.

Medium author Sadhvi Pharasi notes that some places take more than they give in terms of transfer of energy. “Physical environments aren’t neutral containers” she says: “They act upon us.” In her article on why people and places drain you, she notes studies that show that recovery rates are higher when patients can see trees from their windows, and that the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, forest bathing, has been proven to reduce cortisol levels and blood pressure.

She explains, “Most of our daily environments weren’t designed with human energy systems in mind. They were built for efficiency, profit, or someone else’s aesthetic preferences. We adapt because we must, but adaptation comes at a cost.”

The health benefits of “the tribe”

Connection is the glue that binds human beings together. And it turns out that belonging and connection can add years to your life.

The Roseto Effect is a landmark study1 by Stewart Wolf of the University of Oklahoma. Wolf and his colleagues discovered that the inhabitants of a small town, Roseto, Pennsylvania, defied the medical odds of surviving common risk-taking behaviors—that is, the incidence of heart attacks was unusually low even though they smoked, drank and cooked with lard.

The study concluded that the variable that trumped all these health-averse activities was their close-knit community. The small town was made up of a culturally homogenous group from Italy who had immigrated to the U.S. in the 19th century. The thread of belonging from generation to generation anchored them, provided social sustenance, and literally kept them alive statistically longer than most.

Robert D. Putnam did a deep dive on this phenomenon in his 1991 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. His thesis is that, just as the culture in Roseto facilitated mental and physical health, the broader American culture has crippled us, simply by virtue of dislocation and isolation. While we are widely connected virtually, online engagement is qualitatively not the same as the physical connections we experience in the places we love.

The truth is: Social media ≠ social capital.

Think of the connections made through social media to be “shallow-rooted,” and those made through local community ties as “deep-rooted.” Unlike the shallow roots of social media connections, the deep-rooted ties come from multi-dimensional shared experiences, and the deep ties build resiliency in the form of social capital.

Social capital is the intrinsic, hard-to-calculate value of these personal connections. It has been proven more valuable than money, especially in critical situations like natural disasters or political upheaval.

Living in a place you love is the fertilizer for building social capital. Every time you share an experience, a meal, or a sunset with a neighbor, you are building social capital. Every time you learn the name of a neighbor’s pet as you pass them on the sidewalk, or answer a call to run for selectboard, or stand on the sidelines of a Little League game with other parents, you wrap another fiber around the cords of connection.

According to Putnam, the dissolution of these connections, in part due to the concentration of digital relationships, has resulted in a dramatic erosion of the face-to-face social ties that used to be part of every community. He provides statistics that show a dramatic decline in:

Membership in civic organizations

Attendance and membership in places of worship

Political participation, especially in local politics

Social trust

Personal interaction with family and friends

These trends have resulted in a tear in the social fabric that has traditionally supported and upheld rootedness and belonging.

As our cities continue to grow; as more and more of our days are spent scrolling; as our suburbs continue to be filled with houses that are nothing more than holding tanks for commuters; as the wells of true community connection continue to dry up, it will be easy to miss the signs of shallow-rootedness in our lives that make us less resilient to the “slings and arrows” of everyday life.

While Robert Putnam maintains that high-tech forms of connection can be used to support genuine connection, the real roots of community support must be high-touch, fueled by the love of and commitment to our place.

Loving your corner of the world can help save it

The more you feel attached to your neighborhood, town, and surrounding landscape—or bioregion—the more invested you will be in its future.

Bioregions are ecosystems defined by characteristics of the natural environment—rivers, or mountain ranges. Growing up in a particular place—whether it is the forests of the Northeast or the dry lands of the Southwest—embeds the sense-memory of the landscape into our beings. The bioregion literally becomes the land that we love.

For example, I don’t think I could be emotionally tied to that crooked rectangle with the waistline that defines the border of New Jersey, but I could very well feel attached to the Pine Barrens, or the Eastern shore. For this reason, if the Pine Barrens are threatened or even destroyed (as, sadly, much of it was just this week), or if “my” beaches are polluted, I will be more likely to feel grief at the loss and emotionally involved in their restoration.

I have long felt that 350.org, one of the biggest environmental movements of the past couple of decades, is laudable but has conceptual flaws.

Its core argument—the importance of achieving net-zero carbon in the atmosphere—has done too little to create urgency to act. It is both too abstract and too irrelevant for most people in their everyday lives, making it somewhat ineffective as a change agent.

So maybe we must take the argument down a few pegs—specifically, out of the atmosphere and down to the earth beneath our feet.

Perhaps only our emotional attachment to the bioregions of our homelands will make us defenders of them. As it often does, the urgency will only come when the threat is in our backyards.

Alan Thein Durning explains:

Humanity’s failure to act in defense of the Earth is conventionally explained as a problem of knowledge: not enough people yet understand the dangers or know what to do about them. An alternative explanation is that this failure reflects a fundamental problem of motivation. People know enough, but they do not care enough. They do not care enough because they do not identify themselves with the world as a whole. The Earth is such a big place that it might as well be no place at all. [bolding mine]

But he continues with the cure:

The only cures possible may be local and motivated by a sentiment—the love of home—that global thinkers have often regarded as divisive or provincial. Thus, it may be possible to diagnose global problems globally, but impossible to solve them globally. There may not be any ways to save the world that are not, first and foremost, ways for people to save their own places.

To reiterate the quote I used in MM3: You will see beauty:

“In the end, we conserve only what we love.” —Baba Dioum

So ask yourself: Do you love where you live?

I realize that if the answer to that question is “no,” moving is not an option. Most people can’t just get up and hit the road for the place that truly speaks to them.

Part 2, of MM5, Where Do You Belong, to be published in the next week or so, will address:

How we lose our sense of place to begin with.

How to diagnose the degree of your rootedness in your current place.

Ideas and strategies to get to where your heart belongs.

How to recreate your environment and learn to love the place you’re in.

Review of resources and recommendations:

Simone Weil, The Need for Roots: Prelude to a Declaration of Duties Towards Mankind. Routledge, 1952

Infused with Weil’s orientation in Christian mysticism, this book is a plea for a society where people are nourished not just by rights, but by deep connections—to place, to history, to others, and to the sacred threads that make life meaningful,

bell hooks, Belonging: A Culture of Place, Routledge, 2009. From the book jacket: “In this provocative book, hooks explores the geography of the heart.” In it, she weaves her story of her own love for her home with the politics of race and gender and stewardship of the land.

Wendell Berry

The Art of Loading Brush: New Agrarian Writings, Counterpoint, 2017

The Unsettling of America

Home Economics: Fourteen Essays, Counterpoint, 1987

Who better than Wendell Berry to explore the meaning and importance of loving your land and your home base? All of his writings enrich the meaning of place attachment by grounding it in lived experience, moral responsibility, and enduring love for the land.

Yi-Fu Tuan, Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values

An exploration of the emotional bonds between people and place, blending geography, memory, and meaning into a deeply human study of how landscapes shape our values, perceptions, and sense of belonging.

Alan Thein Durning, This Place on Earth: Home and the Practice of Permanence

The reference used in this article is from an excerpt in At Home on the Earth: Becoming Native to Our Place, A Multicultural Anthology, edited by David Landis Barnhill

I enjoyed this anthology: it is a multicultural gathering of voices—Indigenous, Eastern, Western, and beyond—each offering reflections on what it means to belong to a place.

While the 1960s study of "Roseto Effect"showed that strong community bonds were linked to surprisingly low rates of heart disease, later research has raised some doubts about how much social ties alone explained the effect. Still, the Roseto story offers a lasting insight into how connection and community might protect our health in ways we’re only beginning to understand

I’ve moved 22 times in my life, lived in 9 bioregions. I’ve felt the lack of roots. I can’t honestly say that any of those places feel like home to me. I’m thinking carefully about one more, final move….